Kyotoprotokollet 2005

Rättsligt bindande begränsningsåtaganden för utsläpp av växthusgaser (tidsbegränsade)

1:a perioden 2008-2012

2:a perioden 2013-2020 = Dohaändringen

-Har inte trätt i kraft (?)

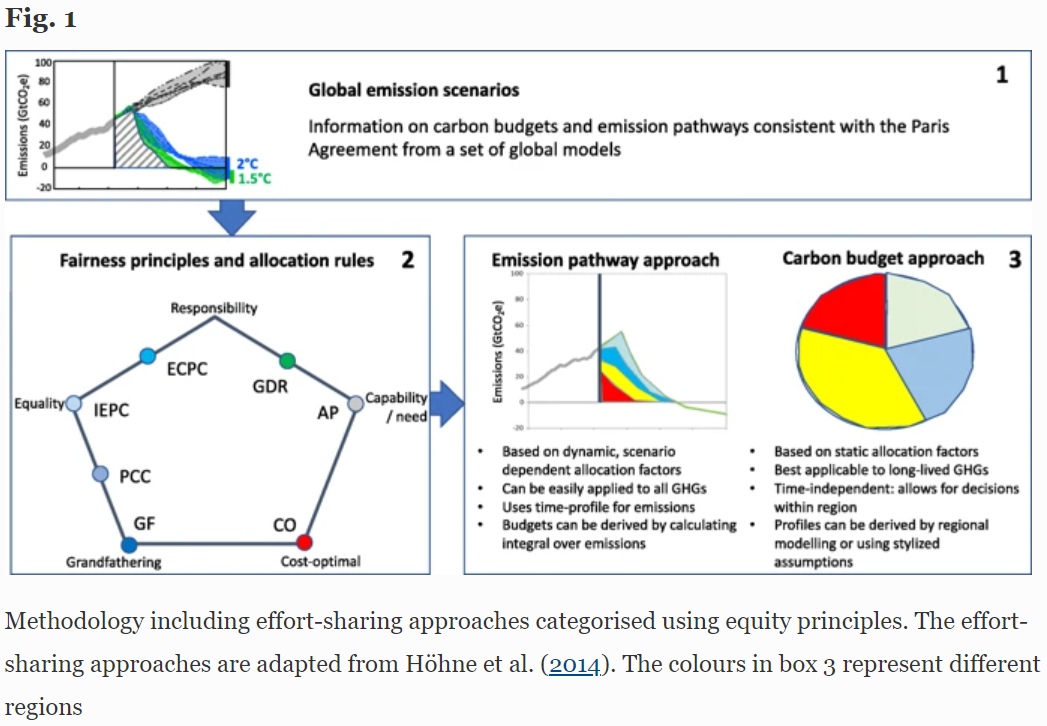

Parisavtalet 2015 (COP 21)

-Globalt, inte tidsbegränsat

-Länder åtar sig att bidra efter förmåga, med ökande ambition

Tre mål (artikel 2)

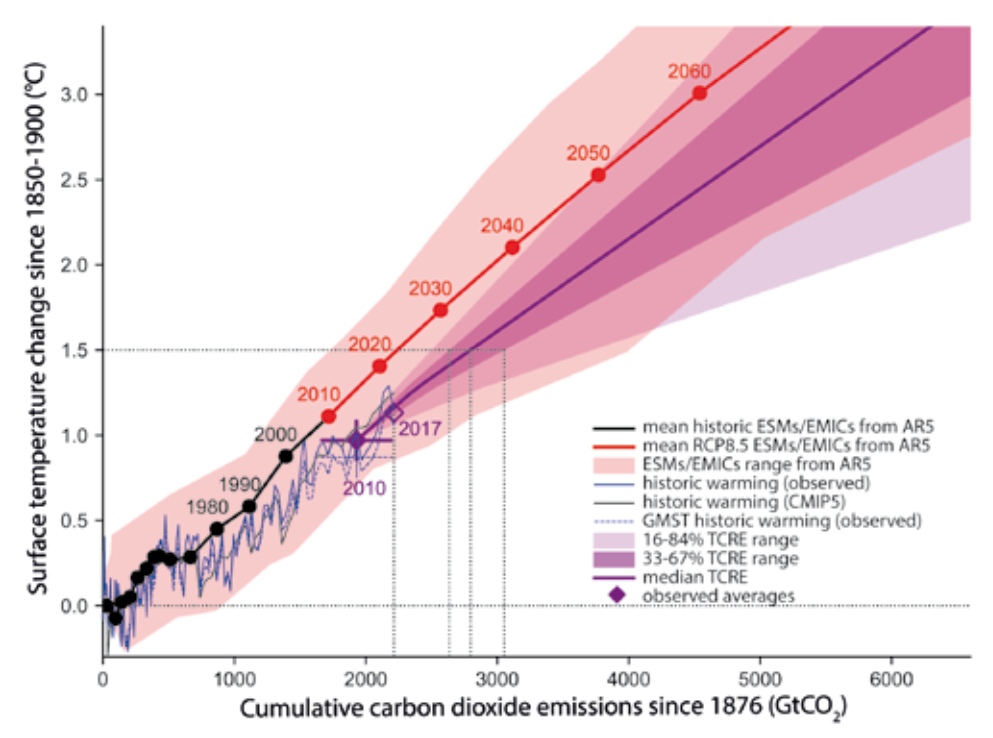

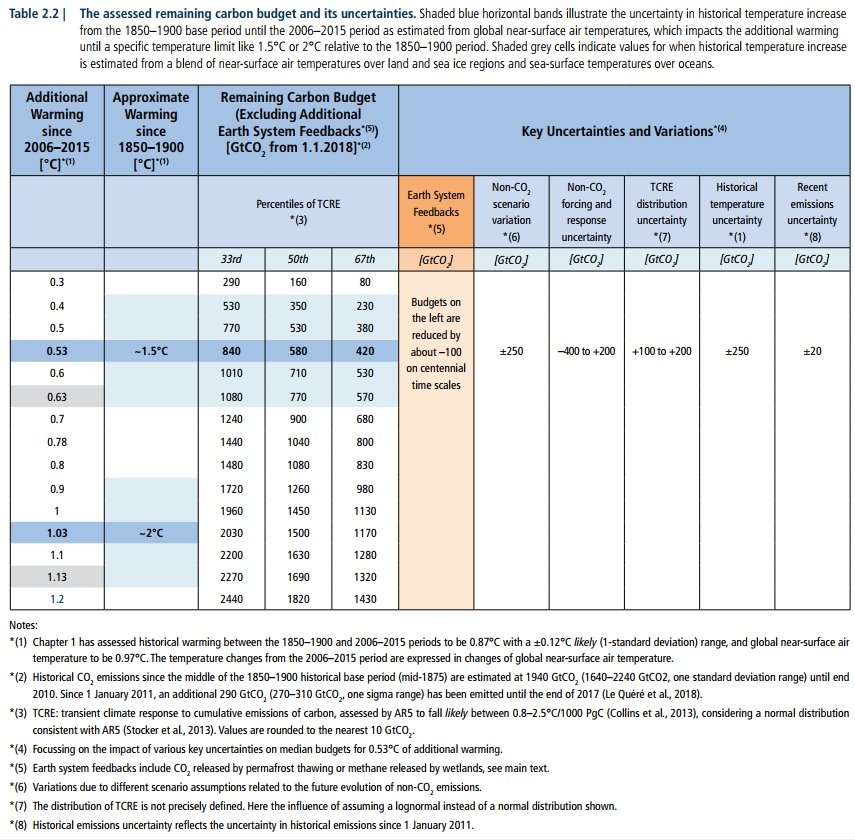

- 2°, ansträngning för 1,5° C

- Hantera skadliga effekter av klimatförändring

- Påverka finansiella flöden för väg mot låga utsläpp av växthusgaser

Arikel 4.1

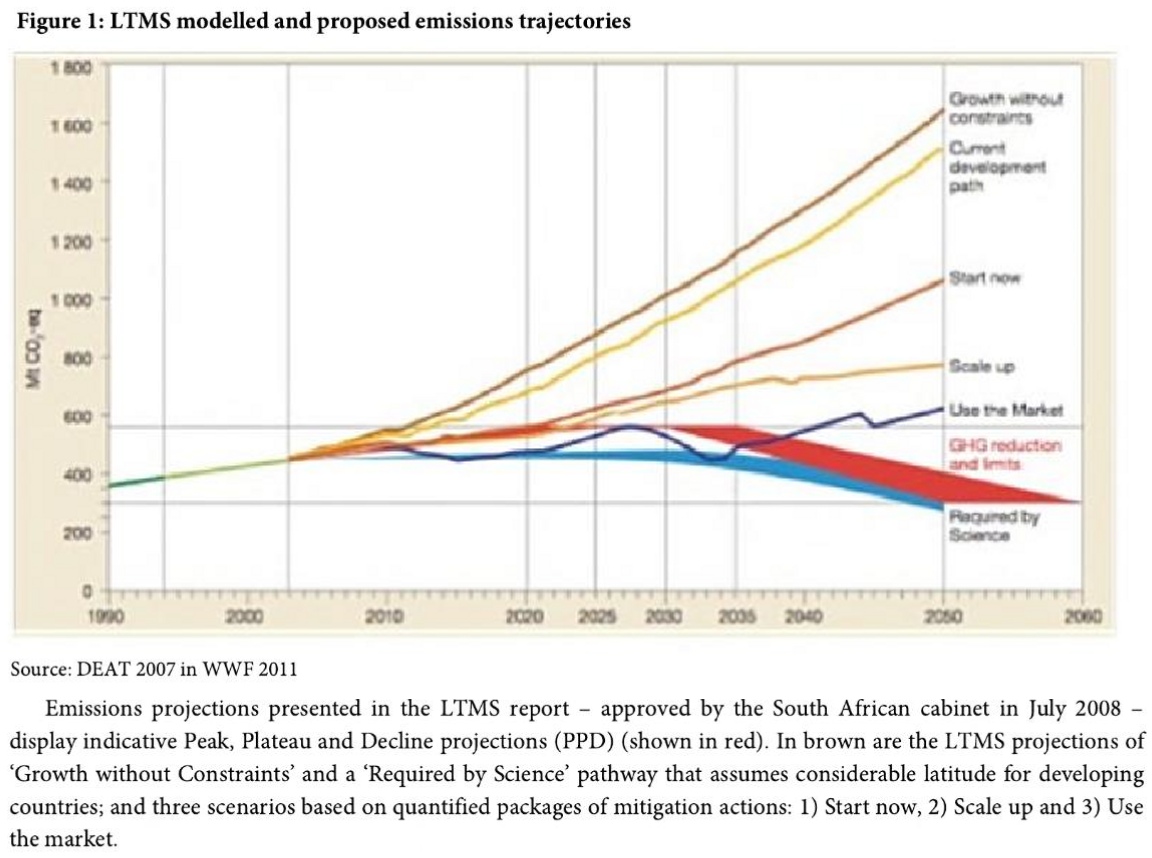

- Parterna strävar efter att nå kulmen för de globala utsäppen så snart som möjligt

- Därefter göra snabba minskningar i enlighet med den bästa tillgängliga vetenskapen

- Uppnå en balans mellan utsläpp och upptag av växthusgaser under andra hälften av detta sekel

- På grundval av principen om rättvisa (=stöd till utv-länder)

- Inom ramen för hållbar utvecklin

- Ansträngningar för att utrota fattigdom

Arikel 4.9

- Varje part ska vart femte år meddela ett nationellt fastställt bidrag (NDC) man avser att uppnå

- Global översyn vart 5:e år

- Sverige har inget eget NDC utan ingår i EU:s NDC